I was in middle school when Apple opened the App Store. Having mowed lawns for a summer to save up for an iPod Touch, I thought the next logical step was to make an app myself. I had no idea how to begin, no problem I was looking to solve, and after a few hours fumbling around in xcode, trying to understand what the documentation meant by ‘function argument’ or ‘API’, that project quickly fizzled out.

Fast forward to June 2020. A few months into Covid-induced lockdown, I’d already baked more sourdough than any one person could ever reasonably need and I was looking for another project. Maybe now, long after the first attempt, it was time for the app development dream to be revived. In the intervening 12 years, Apple released Swift, a much more friendly language for development than the older Objective-C I’d struggled with, and I’d become very comfortable working with Python through some classes in college and now in the Data Science context. Even more importantly, all of that sourdough baking had given me a tangible idea beyond the vague “I should learn how to make an app” motivation.

The Problem

Baking bread, sourdough in particular, can be a fairly meditative exercise full of careful and repetitive steps. We aim to balance the rough kneading needed to build a strong gluten network against the patience required to allow for gentle fermentation and production of delicate air bubbles from the starter. A typical process begins with a ‘slap-and-fold’ - literally slapping the dough against the surface while it’s too sticky to knead, stretching it out, folding it over, and repeating for 5-10 minutes. After that, we enter a cycle of rest periods and strength-building folds. All told, a typical recipe can have 20+ steps:

1) Mix flour and water

2) Rest (this rest without any starter is called an Autolyse)

3) Add starter and mix to combine

4) Rest

5) Slap-and-fold round 1 (5 mins)

6) Rest

7) Add salt

8) Slap-and-fold round 2 (5 mins)

9) Rest

10) Strength-building fold 1

11) Rest

12) Strength-building fold 2

13) Rest

14) Strength-building fold 3

15) Rest

16) Pre-shape

17) Rest

18) Shape into loaves

19) Overnight rest

20) Preheat oven

21) Score and bake

For each step, timing is crucial, aiming for a precise schedule of folding and resting for a predictable result. However, maintaining that precision meant setting kitchen timers 20 different times, and the presentation of rest times in most recipes make it difficult to map out when in the day I needed to be near the kitchen to keep an eye on the dough.

The idea was simple - build an app that can:

- With a single tap, set timers throughout the day(s) of the baking process to alert me when it’s time to head back to the kitchen and take the next step.

- Show me a summary of the complete recipe timeline so I know whether I can actually fit it into my day if I start now, this afternoon, tomorrow morning, etc.

Though this could be useful for cooking just about anything with repetition and complex timing (BBQ comes to mind as another application beyond baking), I was focused on the baking use case, specifically the desire to follow the same recipe timings again and again. Through this purpose I settled on the name for this fledgling project, Rebake.

Development

I won’t spend much time talking about the mechanics of the developement process here, as there are great resources online. I relied most heavily on ‘Develop in Swift Fundamentals’, a book published by Apple themselves, and a free online course from Stanford.

What I will say here is that the process and thinking required for developing usable and maintainable applications is vastly different than the typical data science workflow. When I’m working on a data science process, especially the initial exploratory steps, I’m writing quick interactive code in jupyter notebook. The result of each step has as much influence over the next step - if not more - as my initial plan does. The output of the process is a pipeline that transforms input data, trains a model, then validates its performance. We may build some additional continuous-training and continuous-deployment automation around the pipeline, but the product at the center is still (architecturally, at least) somewhat simple to understand.

At the other side of the spectrum, in app development, I found myself with myriad new challenges like having to manage connections between front-end and back-end systems, working with object-oriented programming practices to a far deeper extent than before, and finding a workable UI layout.

The daunting level of interconnectivity of the various components I was building led me to a greater understanding and appreication for agile practices, as I quickly found the need to start a Twilio board for myself to chunk out the features I wanted to build. Even as a team of 1, I found many familar challenges with vague requirements, difficult integrating fixes into an increasingly complex codebase, and (self-imposed) pressure to get an MVP put together. This time, though, I was looking at these challenges from the new-to-me engineering perspective, and had nobody to blame but myself.

Release

After 5 months, in November 2020, I was ready to release Rebake to the App store. I’d already been using the development copy for a few weeks to great success, and incorporated some UI tweaks suggested by friends and family. I knew this wasn’t going to be a money-making proposition, but just to be able to say I got a couple dollars for something I built, I set a $0.99 price and submitted Rebake for review. After a couple tense days, it was approved and listed on the app store to a flurry of…

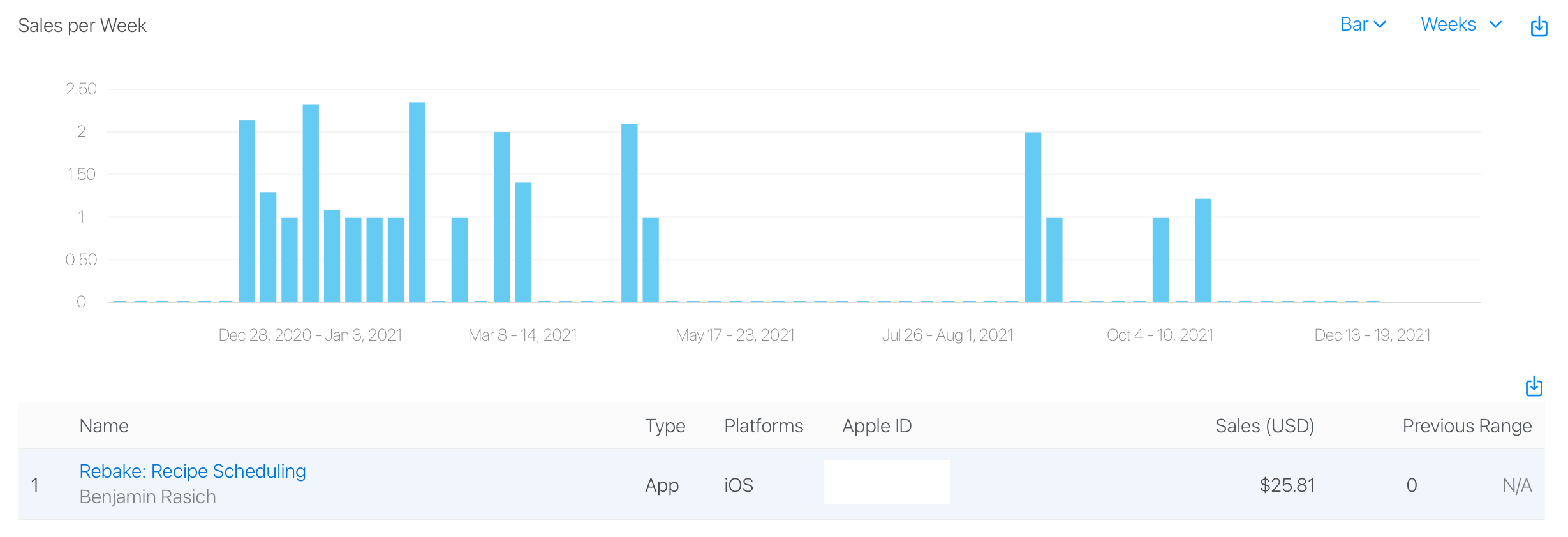

…nothing. I didn’t expect greatness, I didn’t expect go viral, but I was definitely hoping against hope to see my first dollar on day 1. Or week 1. Or month 1. But then - December 7, 2020, it happened. I checked my dashboard to find that I’d sold 1 copy to someone in Brazil. With the potential exception of the first time the tooth fairy visited, this was easily the most exciting dollar (ok, 70 cents after Apple took their cut) I’d ever recieved. I was over the moon, and immediately put it towards $20 of celebratory takeout.

After a full year, I ended up with $25.81 in sales, translating to $20.22 after Apple’s cut.

On the other side of the balance sheet, we have the $99/yr cost to list an app on the App Store and the marginal ~$200 I spent on a refurbished Macbook over an equivalent PC to even be able to start this project. All told, then, not the greatest ROI I’ve ever seen. But this was never for the profit (no matter how much I hoped against hope to be wrong on that account), this was a learning experience, and what a learning experience it was.

Findings

- App development is hard. Project management is hard. Data scientists working on models indended for production deployment should try this (or something similar, like building a web app) to get a hands-on feel for the complications our engineering partners have to consider as a part of their responsibilities.

- Marketing budgets are huge for a reason. Very few people saw my app store listing in their search results. Even fewer clicked through to my product page, and fewer still were willing to fork over their cash to give it a try. Companies spend over 10% of their budgetes on marketing to boost each part of that funnel by just a few basis points at a time. Seeing 12,350 potential customers turn into 1,500 page views turn into $20.22 in proceeds was a painful illustration of the necessity of that spending.

All in all, this was one of the most fun and rewarding projects I’ve undertaken. Seeing the idea through to a finished product was awesome, and the rush of getting positive customer feedback and feature suggestions will be tough to beat. The fact that ~25 people were willing to pay me for it is the icing on the cake, and at least it covered my celebratory takeout.